GPS waypoints (also called POIs) for use with Canadian Rockies Geology Road Tours, instructions for preparing Ben’s rock-testing acid, and updates and corrections to the book

Feel free to copy or download the information below.

Waypoints

These are the latest waypoints/POIs, with all corrections and updates included. One of the files also includes the tracks I recorded on my GPS unit as I followed the various highways. These tracks are generally truer than the highway alignments given on the current federally issued topographic maps.

You have four choices in downloading the waypoints:

Choice number one: GDB file

If you have Garmin’s “BaseCamp” or “MapSource” program on your computer, and a compatible GPS receiver with download capability, click here.

After downloading the file and saving it, run BaseCamp or MapSource and open the file. The waypoints and tracks should be displayed. Connect your GPS receiver and download the waypoints and tracks to it by clicking on the program’s download icon and following the directions. Save the file before closing the program, in case you want to use it again.

Some of Garmin’s automotive GPS units can receive waypoints as “POI”s, meaning “points of interest.” Garmin provides a program called “POI Loader” for converting GDP files to POI data and loading it into the auto unit. Information at www.garmin.com. (Click on Support, Updates & Downloads, and Mapping Programs to locate the free download.)

Choice number two: GPX file

If you have some other GPS program on your computer, and it cannot open the GDB file above, click here.

After downloading the file and saving it, run your GPS program and open the file. This format is GPX, used for the exchange of GPS data among various programs. GPX files can include tracks, but the file I have provided here does not, because tracks may cause problems on devices that do not use BaseCamp or MapSource. If your program can open this file, you may be able to download it to your GPS receiver. If this works, save the file before closing the program, in case you want to use it again.

Choice number three: conversion with GPSBabel or PoiEdit

If your GPS program will not read the GDB or GPX files, you may wish to visit www.gpsbabel.org and purchase a copy of GPSBabel. This inexpensive shareware program, which I have not tried but which has been widely acclaimed, is able to convert many GPS data formats to one another.

Those of you with TomTom automotive GPS units might like to try downloading the shareware program PoiEdit, which can convert GPX files to the OV2 files that many TomTom receivers use. For your convenience, I have done this conversion for the latest waypoints. Download it by clicking here.

Regardless of the conversion program you use, download and save the two previously listed waypoint files. Then try opening them in GPSBabel, PoiEdit or another conversion program and saving them in a format your GPS unit can use.

Choice number four: manually enter waypoint coordinates from a TXT (text) file

If none of the methods above works, you still have one more choice. Click here.

After opening the file, save it to your computer. This is a TXT file, plain text. If you are running Windows, double-clicking on the file will open it in the Notepad program. The latitude/longitude coordinates of each waypoint will be displayed, along with a lot of other info. See if your GPS program — or the receiver itself — will allow you to manually enter the waypoint number and its lat/long coordinates, which are all you need. If so, you can manually enter the waypoints/POIs along any of the tours in the book.

Rock-testing acid

To download my instructions for mixing up a dilute solution of hydrochloric acid for testing rock to see whether it contains the minerals calcite or dolomite, click here.

Corrections and updates

In December 2009, the second printing of Canadian Rockies Geology Road Tours became available, incorporating corrections to the first printing (2008). Still, some errors and unclear statements sneaked through into the new printing. You may wish to pencil in the following updates.

Page 48, first paragraph under “Rocky Mountain Trench,” last line, change “visible in photos of the Earth taken from the moon” to “easily visible from space.”

After many years of passing along a story that one of the Apollo astronauts radioed mission control while in lunar orbit to ask about a straight line in northwestern North America, I chanced to view the Apollo photos of the Earth as seen from the Moon. The Rocky Mountain Trench was not discernible in them.

I contacted NASA. William P. Barry, NASA’s chief historian, checked the mission transcripts himself, then had them checked very carefully again by one of his staff. As he told me by e-mail on 30 Jan 2014, there is “nothing remotely like a reference to a Rocky Mountain Trench” anywhere in the transcripts.

The Rocky Mountain Trench can certainly be seen from space. I could pick it out in images taken from 1.5 million kilometres away by NASA’s DISCOVR satellite. But no astronaut has reported seeing it from the Moon.

Page 100, in the illustration at the bottom of the page, the annotation “Grotto Mountain 2706 m” should be moved 1.5 cm to the right, so it is above the true summit of the mountain.

Page 112, the label “WindTower” should be “Windtower.”

Page 118, in the photo of the Three Sisters, the elevation of the highest, rightmost summit should be 2936 m.

Page 119, in the illustration of Mt. Rundle, the summit elevation should be 2949 m. The same error occurs in the photo of Mt. Rundle on page 127.

Page 155, with thanks to Ray Price, of Queen’s University. Re the dykes, Ray doubts that these are actually made of carbonatite, but he is unsure of the exact rock type. Can anyone help nail this down? If you are that person, please e-mail me at ben@bengadd.com.

Also on this page, in the same paragraph as the one about the dykes, the phrase “on the trailing edge of the moving continent” is technically correct — the motion of the continent was relatively eastward (southeastward at the time, when the continent was turned about 90 degrees clockwise from its present orientation), so the western edge was the trailing edge — but the edge was at a subduction zone (see the footnote on page 73), which was more of a leading-edge, active-margin situation than a trailing-edge, passive-margin situation.

Page 160 and 161, change all occurrences of “tufa” to “travertine,” a more accurate term for this kind of deposit.

Page 165, in the sidebar “About the Rocky Mountain Trench,” first paragraph, change “The Rocky Mountain Trench is visible from the moon” to “The Rocky Mountain Trench can be seen from space.”

Page 193, in the second, third and fourth paragraphs, change “Barrier Mountain” to “Mount Baldy.” Do this also in the next-to-last paragraph on page 208. In the index, add item “Baldy, Mt. 193, 208,” and under the item for Barrier Mountain, add “See also Baldy, Mt.”

Mount Baldy has been the official, gazetted name for this peak since 1984. The name was adopted by the Geographic Names Board of Canada despite (a) not following its own rule that “Mount” is reserved for peaks named after people, and (b) despite “Baldy” being such a mountain-name cliché. Until I checked the official-names website (https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/earth-sciences/geography/place-names/search/9170) I could not believe that this was actually the correct name.

But wait, there’s more. The name I knew the mountain by, “Barrier,” was not just a mistake on my part. It was actually an older unofficial name. It could not be applied officially for what became Mt. Baldy because it had already been applied officially in 1956 to a peak 82 km farther north (Barrier Mountain). Okay, let’s not use the same name for two different mountains. But “Barrier” also wound up being adopted in the same year, 1956, for the name of the reservoir at the foot of what was then called “Barrier Mountain” informally and is now formally Mt. Baldy.

Not only that, there’s a summit in the foothills officially named Old Baldy Mountain in 1941 that’s 42 km northeast of, get this, Barrier Mountain!

Thus has confusion been sewn. It will continue to be reaped.

Page 213, in the photo, change the label “~2660 m” to “~2500 m.” The cabins seen in the photo have been removed. In the photo caption, in the sentence beginning “The unnamed summit,” change “Mt. Head itself (2782 m), unseen 2.5 km to the north” to “Holy Cross Mountain (2650 m), unseen 800 m to the north.”

Page 220, in the illustration of the triangle zone, the photo is not properly aligned with the diagram. When I took the photo I thought that the centre of the triangle zone lay along the valley of Nelson Creek and Callum Creek (low area in the photo), and that this view showed the triangle zone perfectly. But in fact the rock in the first two ridges to the right of the valley dips eastward, not westward. Those ridges are actually still in the eastern part of the zone. The third ridge right of the valley is underlain by southwest-dipping rock, so it’s in the western part of the zone. If the photo were shifted about 4 cm left it would better approximate the true position of the zone.

Page 248, second paragraph, my assumption that Pierre Jean de Smet was writing about what we now know as the Kootenay Group was incorrect. A close reading of de Smet’s account of his 1845 travels revealed that he did not follow the Flathead River into the Rockies. Rather, he was moving along the Kootenay River in the Rocky Mountain Trench, where the Kootenay Group does not outcrop. He may actually have been writing about coaly beds in some other rock unit exposed in the Rocky Mountain Trench.

Still, de Smet’s travelogue, published in 1847, does represent the earliest descriptions I could find of rocks and minerals in the Canadian Rockies. If a reader knows of anything earlier, please contact me about it. The e-mail address is ben@bengadd.com.

Page 257, end of the second paragraph. Ray Price has pointed out that big normal faults are not “unknown in the eastern front ranges,” at least not south of the Bow River. The Erickson Fault, found along Hwy 3 at waypoint CP 29, is such a fault, and it is found only 12.7 km west of the mountain front, definitely in the eastern front ranges. I should have used “uncommon” (as I did on page 262) instead of “unknown.”

Page 258, fourth paragraph. Referring to Montania as “an island” may give the wrong impression. Ray Price points out that this region of emergent land reached at least as far west as Chewelah, in northeastern Washington. The boundaries of Montania have not been precisely determined. This landmass may have been part of the ancient North American craton.

Page 259, second paragraph, second sentence, remove “black shale of the.”

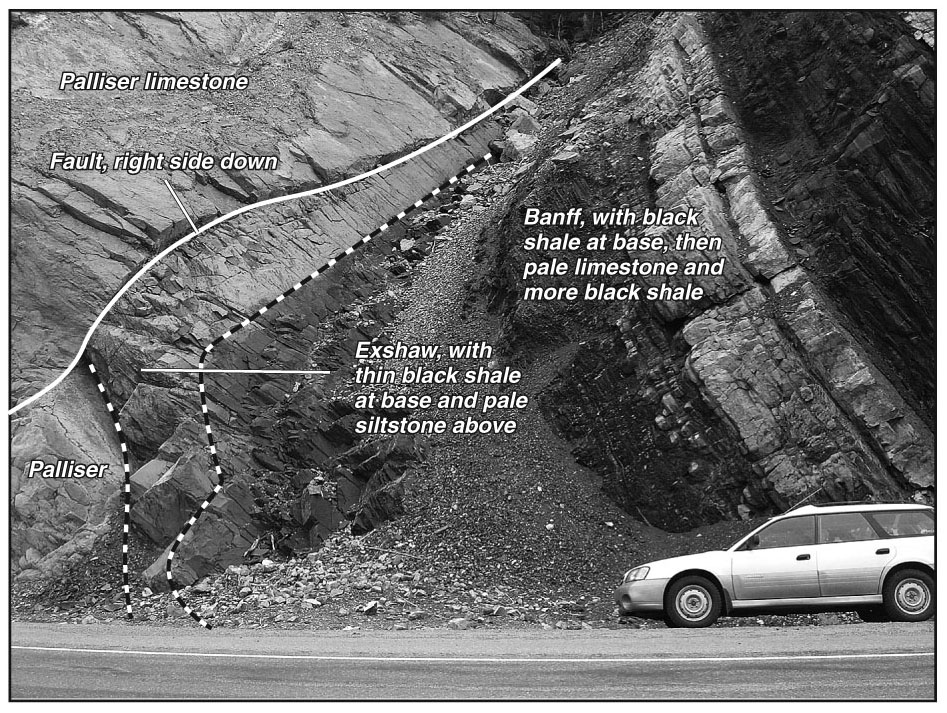

Also, the annotation on the photo is not correct. I was fooled! What looked obvious — the boundary between the Palliser Formation and the Exshaw Formation, and the boundary between the Exshaw Formation and the Banff Formation — is not. The photo below shows the true relations. A small fault runs through the rock. (In the book, this fault passes between the words “Palliser” and “limestone.”) On the right side of that fault, the Exshaw has been dropped down a couple of metres. By chance, the top of the Exshaw lines up pretty closely with the top of the Palliser. So what I had marked as the top of the Palliser was, on the right side of the fault, actually the top of the Exshaw. Everything from there rightward is in the Banff Formation. Also, the Exshaw is quite thin here — only a couple of metres, thinner than I thought — so the whole unit can be seen lying atop the Palliser. Again, my thanks to Ray Price, who knows this cut well and caught the error.

Page 307, in the photo, the elevation given for the SE summit of the Kaufmann Peaks is incorrect. It should be 3109 m. (3094 m is the summit elevation of the NE peak, mostly hidden behind the SE peak in this view.) Thanks to Graeme Pole for spotting this error and the next one.

Page 310, in the third paragraph, the elevations of both Kaufmann Peaks are given incorrectly. The left (SE summit, officially “Kaufmann Peaks, South”) should be 3109 m. The right (NE summit, officially “Kaufmann Peaks, North”) should be 3094 m. The elevations are shown correctly in the top photo on page 311.

Page 335, second paragraph, phrase in the third line “For more about the Exshaw.” should be removed.

Page 341, dagger symbol at the end of the text by the fourth dot should be moved up to the end of the text by the third dot.

Page 345, as of 2013 the Kitchener Slide Viewpoint has been taken over by Brewster Travel Canada and turned into a “skywalk,” meaning a walkway with a transparent floor cantilevered out over a drop. The viewpoint is no longer a public pull-off open to anyone at no charge. One cannot simply stop there and view the geology. One must either pay a fee to the corporation and board a shuttle bus at Icefield Centre, or park a kilometre north at Tangle Falls and walk back up the highway (or along a trail) to a much-restricted free-viewing area.

Page 404, in the last paragraph, Pocahontas did not marry John Smith. She married a colonist named John Rolfe. The story that she saved Capt. Smith from execution by her tribespeople is likely false.

Page 444, second paragraph, change “and the yellow or orange mineral goethite (HFeO2)” to “and the yellow or orange stains of limonite (FeO(OH) · nH2O).”

Page 499, beginning of the third paragraph, “kilometre 227” should be “kilometre 277.” Thanks to Aaron Springer.

Page 545, in the Jurassic section of the time line, move the “200-146” item to the top of the box.

Page 550, in the correlation chart, move the 488 Ma line up a half-centimetre or so, making the Survey Peak Formation late Cambrian and early Ordovician.

Page 556, in the list of maps for the Trans-Canada Highway, after the first item add “82N Geology of the Main Ranges of the Rocky Mountains from Vermilion Pass to Blaeberry River and Bow Lake, British Columbia – Alberta GSC 1368A Cook 1973.” Also add this map to the list for the Vermilion Pass route, same page, and to the list for the Icefields Parkway, page 557.

Also on page 556, in the last item in the Trans-Canada Highway list, change “82O5E” to “85O5W.”

Page 559, the website for freely downloading GSC maps has changed, as have the instructions for using it. Here are the new instructions.

- Go to geoscan.nrcan.gc.ca.Click on English or French as desired.

- If choosing English, the page that opens should indicate “GEOSCAN: Basic Search.” In the “Basic search” box, type in the number of the map you want, e.g. “1865A”. (This is the number for Margot McMechan’s excellent geological map of the foothills and front ranges southwest of Calgary.) Press Enter.

- On the “Results” page that appears, you should see the title of the map you want, in this case Rocky Mountain Foothills and Front Ranges in Kananaskis Country, West of Fifth Meridian, Alberta. Click on it.

- Detailed information about this map comes up. Just below the map title, click on “Downloads.”

- You see a thumbnail view of the map. Clicking on it will start downloading a PDF of that map. When the map appears, right-click anywhere on it and select “Save As.” Pick a folder or just save it to the desktop for now.

- The filenames that GEOSCAN uses for downloaded material are rather cryptic. You might want to change the name of the file to something like the map name I used in the list of maps in the book.

Page 575, second column, change index item “tufa 160” to “travertine 160” and move it up to just before “treeline.”

Finally, please note that the publisher information for Canadian Rockies Geology Road Tours has changed. New:

Verdant Pass Ltd.

202 Grizzly Crescent

Canmore, AB T1W 1C1

403-609-4449

ben@bengadd.com

_________________________________________________________________

Happy geologizing!

— Ben Gadd